On January 21, one of North Carolina’s most dedicated advocates, Gerda Stein, will leave her long-time post as Director of Public Information at CDPL. Here, Executive Director Gretchen M. Engel pays tribute to a colleague and friend who has left an indelible mark on our movement — and whose kindness has touched many people who faced execution.

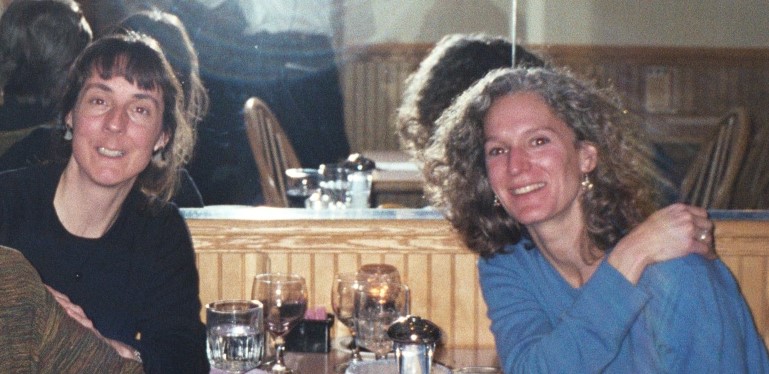

Gerda Stein with Henry McCollum, a longtime CDPL client who was exonerated in 2014 after 30 years on death row

By Gretchen M. Engel

This is not a eulogy.

That said, it is with deep sadness that I mourn, after 30 incredible years of service, Gerda Stein’s departure from CDPL later this month.

I met Gerda in the fall of 1991, when I was law student interning at Ferguson Stein. Gerda had just been hired as a mitigation investigator at the NC Resource Center. I had no idea then that Gerda would become one of my dearest friends and colleagues.

In the early 1990s, many men and women received the death penalty from juries who knew little about their lives. Gerda changed that. She worked with the UNC school for social work, organized trainings, consulted with capital defense teams and, through perseverance and patience, institutionalized the practice of mitigation investigation in capital cases in our state. (Gerda would be the first to point out that she was not the only one involved in these efforts. Of course she was integral to these efforts. And, besides, this piece is about Gerda.)

Gerda was also a practicing model for new recruits. She comforted Henry McCollum through years of depression before he was exonerated in 2014. Her empathy for Norris Taylor, a desperately abused and mentally ill man, was legendary. When he died of natural causes in 2006, the prison didn’t know any family members to call. So they called Gerda. Gerda was the mitigation investigator and later a member of the successful clemency delegation for Robert Bacon and, when Robert was dying, his sister likewise contacted Gerda.

The work was demanding and emotionally exhausting. Our clients’ childhoods are so often horrifying and the daily exposure to stories of degradation and violence is corrosive. Eliciting those stories and then helping to present them to jurors is hard even when you win. And in the 1990s, we often lost.

Gerda took a brief hiatus from CDPL sometime in the late 1990s. It’s hard to remember now, because it feels to me like she was always there: She was there the nights my clients Harvey Green and Quentin Jones were executed. Along with his attorneys and daughter, Gerda was with Dawud Abdullah Muhammad the night he was executed. Between 1992 and 2006, nearly 40 times, at two o’clock in the morning, Gerda was there.

In 2000, Gerda came back to CDPL to take on a new challenge, telling the stories she knew so well to the public at large. This was shortly after the national backlash to Benetton’s “We, on Death Row” ad campaign, and becoming CDPL’s public education director was no small challenge. Back then, lawyers for people facing the death penalty were loath to speak to the press because their stories invariably and exclusively focused on the gory crime facts and suffering of people who’d lost a loved one to murder. And the execution machine was burning at full throttle: in just over four months in the fall of 2003, North Carolina executed seven men.

Gerda brought her compassion, work ethic, fearlessness, and vision to the task and, over the years, media coverage of capital cases has dramatically changed. First there was the series in the Charlotte Observer exposing the under-resourced state of capital defense and the endemic racism in our cases. Later the News & Observer ran a series on prosecutorial misconduct and wrongful convictions in death penalty cases.

In clemency campaign after clemency campaign, Gerda worked with defense teams to expose injustices in individual cases. Among many hard losses, Gerda was there to see the Colosseum in Rome lit up after Governor Hunt granted clemency to Wendell Flowers, to see Tim Allen and Pat Jennings sentenced to life after they’d each spent two decades on death row, and she was there to see Alan Gell and Henry McCollum walk free after years of wrongful incarceration. And she’s been here to see 15 years with no executions, 15 more years of life for Blanche and Dan and Phil and Priscilla, and so many others.

Because our names both start with a hard “G,” I’ve often been called Gerda over the years – although never “Girla,” Norris Taylor’s pet name for Ms. Stein. For years after we made a trip to Washington D.C. to investigate Tim Allen’s case, I would explain on the phone to Tim’s family members, “I’m Gretchen. No, the pregnant woman was Gerda. I’m the other one.” How flattering it’s been to be confused with the most dedicated and powerful advocate and kindest human being I know.