Gretchen’s last day at CDPL was Friday, August 29, 2025. While there will be more to come regarding our transition, we wanted to share this message from Gretchen. In this video, Gretchen reflects on her 33 years representing people facing the death penalty and being a part of the capital defense community.

Cultivating Compassion Through Remembrance and the Arts

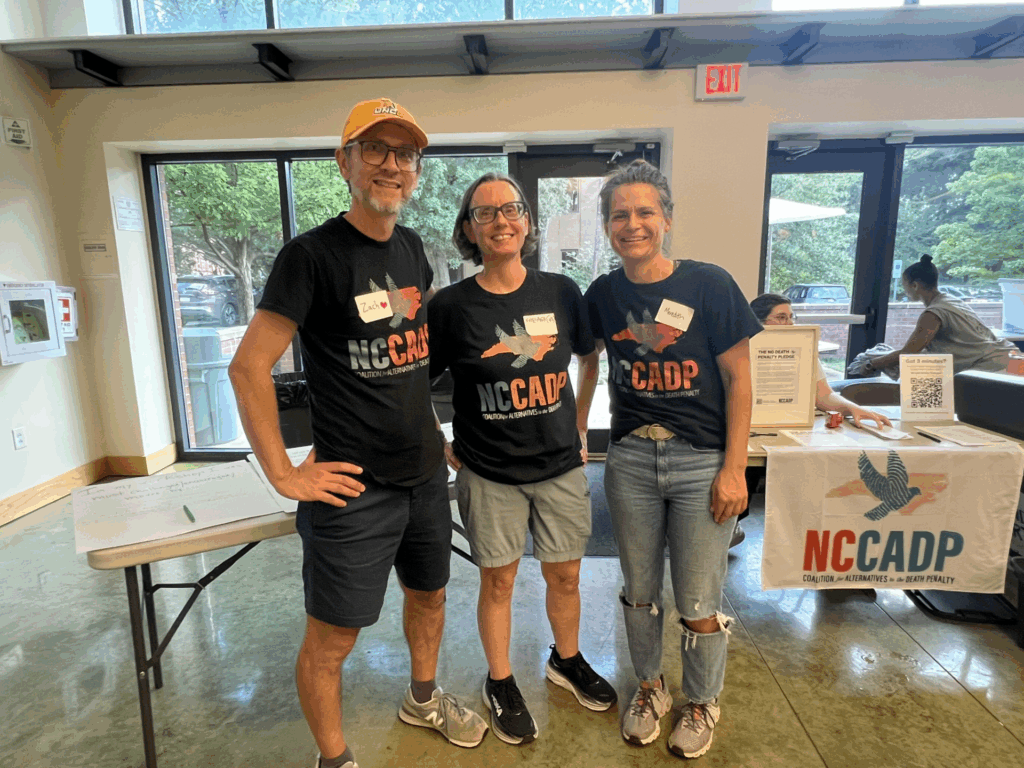

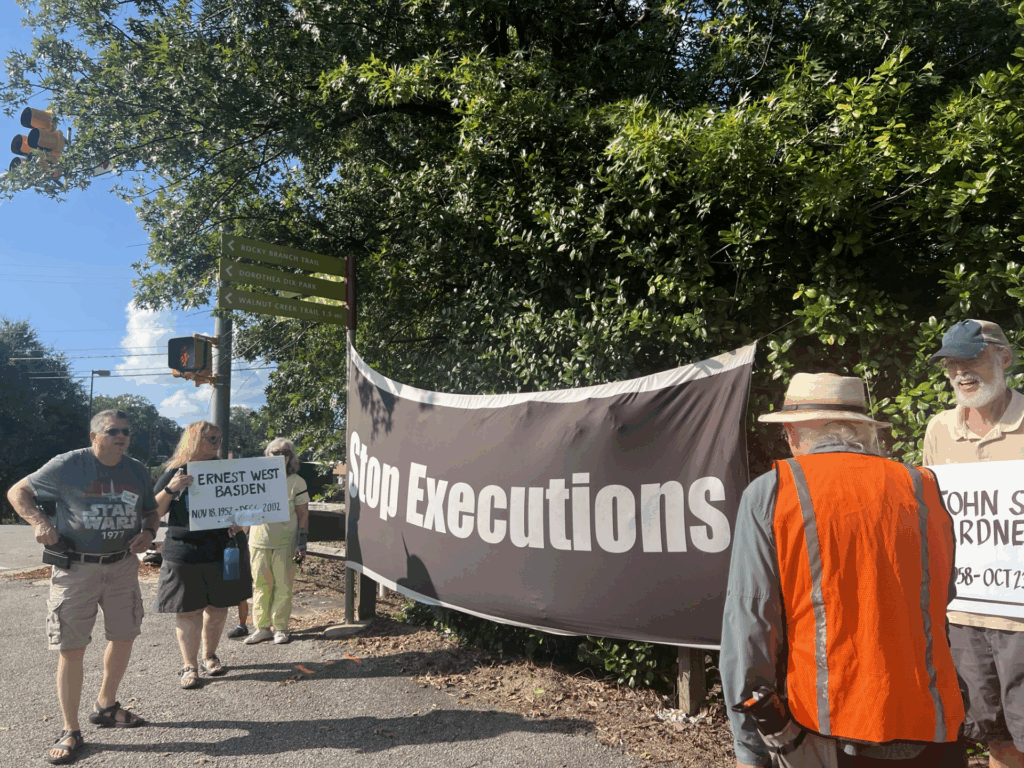

On Saturday, August 16, a few of us from CDPL gathered at Pullen Memorial Baptist Church in Raleigh to join NCCADP’s day of workshops, remembrance, and advocacy. There was an eclectic mix of people, ranging from individuals exonerated from death row, family members of people who have been executed, and those motivated by religious persuasion. As we walked from the church to Central Prison, where 120 men sit on death row, we carried signs bearing the names of the individuals who have been killed by the state of North Carolina and then read them out loud together.

It would be remiss of me not to acknowledge that each name lifted up represents multiple deaths, albeit persons killed by different means. We do not forget those names unsaid. Rather, when we remember those killed or condemned to be killed by the state, we lift up all victims of violence, steadfast in our belief that violence of any kind only breeds further harm. When we practice this unwavering sense of dignity in the other, we cultivate the compassion and empathy needed to break the tenacious cycle in which we find ourselves.

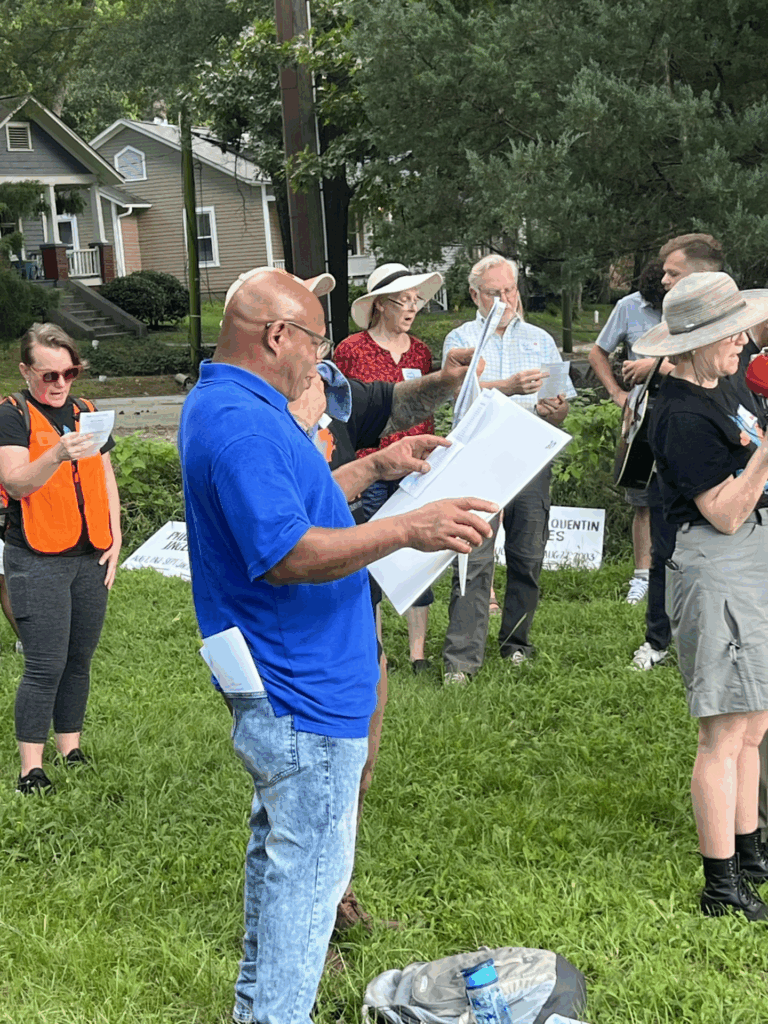

Glen Edward Chapman was one of the exonerated men who walked with us on Saturday. When I asked him how he thought about the victims in his case, he told me he always takes care to mention their names whenever he speaks publicly, recalling with disdain that the state consistently referred to them as simply “prostitutes.” The call for death penalty abolition is not one that overlooks victims, but one that sees past the deceiving binary between victims and offenders.

Having known Ed for a couple of years now, I have heard him reflect on the community he built during his 13 years on death row. Many in his situation, innocent and living with men convicted of murder, might fight to distinguish themselves from the others. Instead, Ed talks fondly of the relationships he developed, even considering some of the men his family. In that vein, he told me how painful it was whenever someone was executed. In the moments leading up to an execution, Ed and the others held a memorial service for them, going around and saying a cherished memory of the brother they were about to lose. At 2:00 a.m., the approximate time of execution, Ed would point towards his window and say, “I’ll see you soon.”

Against this backstory, I watched Ed read the names in the relentless August heat, and I considered the weight he must carry.

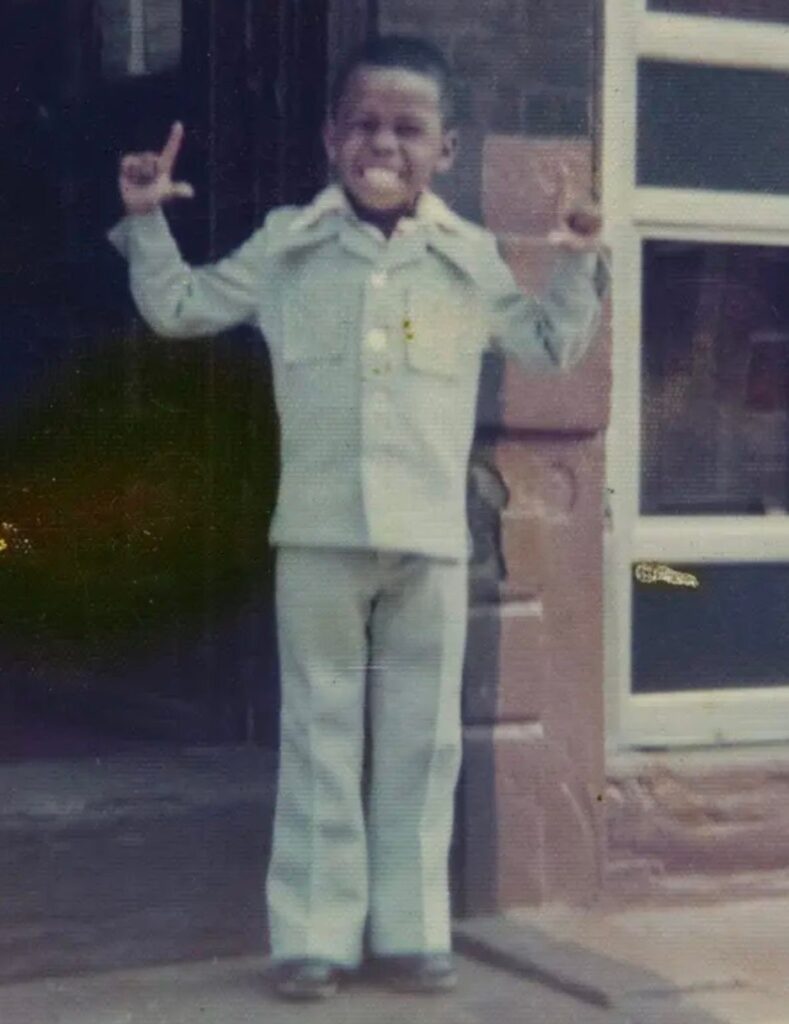

At the same time, just on the other side of the Triangle in Chapel Hill, Lynden Harris, founder and director of Hidden Voices, was on the eve of premiering A Good Boy. Harris spent time on death row as a volunteer, conducting writing and story-telling workshops. Much like Ed, her time there led her to what some may characterize as an unexpected sense of connectedness and insight. Harris would first write Right Here, Right Now: Life Stories from America’s Death Row, a collaboration between herself and over 100 people on death row across the country. Based on the conversations it generated, Harris decided to write a piece centered on the perspectives of individuals with loved ones on death row, and A Good Boy was born.

The musical is set in the waiting room at Crossroads Correctional, where two mothers and a male family member wait to speak with their loved ones on death row under the watchful eye of an over-worked corrections officer. A fourth visitor comes to retrieve a picture of herself with her brother, who was executed the night before. Amidst the helplessness and uncertainty they experience as they wait, the visitors’ conversations amongst one another and with the guard reveal harrowing truths about capital punishment, our carceral system, and how they both impact and are impacted by complex social fabrics. These conversations also illuminate a side of life on death row outsiders don’t get to see, such as diverse interests, including NPR, jazz, and politics, religious conversions, and friendship.

The main message crystallizes, though, through an unlikely character: the corrections officer. While it may seem like the guard is removed from the world of pain and suffering inhabited by the visitors and their incarcerated/executed loved ones, he shatters this illusion when he starts talking about his own childhood. He shares just enough details to expose the hatred and desire for vengeance he harbors towards his father, a vitriol that appears to overlap with the disdain he carries for those incarcerated at Crossroads Correctional. As the audience learns more about each character, they come to see that humanity is a web of brokenness, and the path to healing lies not in retribution, but “in a little mercy and a whole lot of grace,” the refrain of the musical’s last number.

Mercy and grace, however, do not erase pain and suffering. Nor are they incompatible with public safety. Creating safe spaces for healing is hard work. But taking the time to remember and reflect on one another’s humanity and the humanity of those to whom the basic right of breath has been denied, not to mention those who love them, might be the best place to start.

So thank you to NCCADP, Ed, and Hidden Voices for lifting up the humanity of our clients and their loved ones. We are all the better for it.

Remembering James E. “Fergie” Ferguson

It is with great sadness, yet immense gratitude, that we write to commemorate the life of James E. “Fergie” Ferguson II (1942-2025).

Nationally renowned as one of the most prominent civil rights attorneys of his generation, Fergie’s commitment to racial equality was born, raised, and anchored right here in North Carolina. Growing up in the Jim Crow South, Fergie experienced the acute pain of being a person of color in a society divided by race. Refusing to make peace with hatred, Fergie became a catalyst for unity as early as junior high school, organizing an integrated committee to discuss issues of race.

After graduating from Columbia Law School in 1967, Fergie helped found North Carolina’s first racially integrated law firm. He was a key part of litigation teams that secured desegregation in Charlotte’s public schools, defended and then won pardons for the Wilmington 10, and challenged Duke Energy’s racially discriminatory hiring practices. Always one to see beyond his own immediate circumstances, Fergie also co-founded South Africa’s first trial advocacy program, training scores of attorneys during and after Apartheid.

CDPL is especially grateful for how Fergie helped us champion the Racial Justice Act (RJA) in 2009. As Fergie noted, advocating for the RJA “was a unique opportunity to do the very thing that I’d gone to law school to do, that is, to try to address racism in a direct way.” In this spirit, Fergie continued to fight so that the RJA might make a tangible difference for the people on death row, securing four life sentences under this landmark legislation.

Fergie was stubbornly optimistic even when the progress he saw materialize seemed to come undone. As we reflect on Fergie’s incredible witness during these uncertain times, we are encouraged to keep fighting for the dignity of each individual and working to eradicate the pernicious racism that runs through our criminal legal system. As such, we are hopeful that others might also find inspiration in this life well-lived.

Thank you for your partnership as we continue to fight Fergie’s fight. We need you now more than ever.

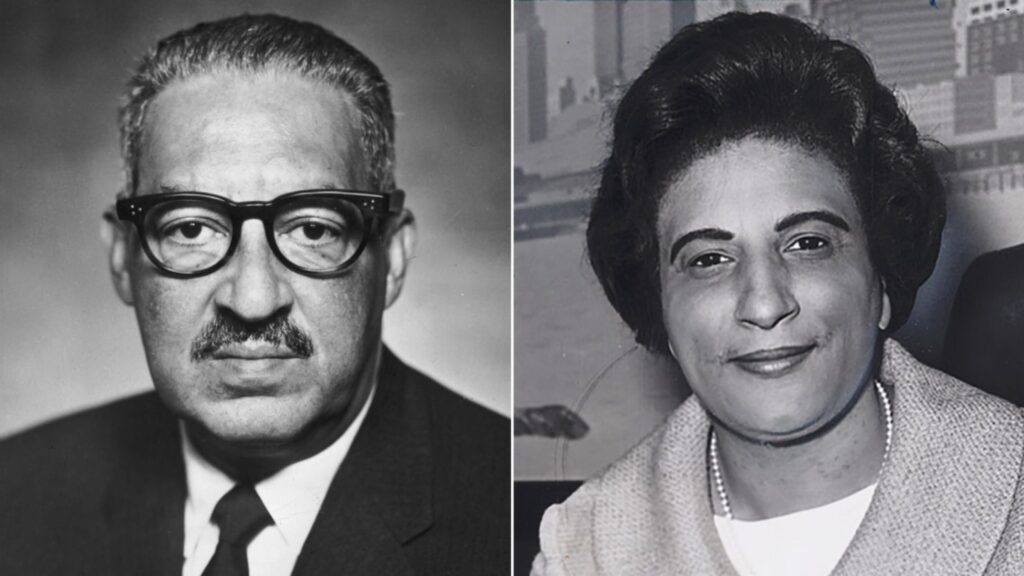

CDPL Hosts Marshall-Motley Scholars

Ashley Conyers, a rising third year student at NCCU School of Law, and Deksyos Damtew, a rising second year student at UC Berkeley School of Law, have spent the summer months interning at CDPL as part of the Marshall-Motley Scholars Program. This prestigious program, named after Thurgood Marshall and Constance Baker Motley (pictured above), is facilitated by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The program is committed to “developing a cadre of civil rights attorneys whose work in the American South will usher in transformational change” by supporting students throughout their time in law school and beyond.

Convinced of the strong ties between slavery, lynching, and the death penalty, capital work is a natural fit for Ashley. Her interest in CDPL was sparked last year when one of our legal interns told her how working here motivated her to do impact litigation and capital defense. Then CDPL Board Vice President Terrica Ganzey invited Ashley to be her “plus one” at our annual fall fundraiser, where she was impressed by the significance of our work and the kindness of our staff. Fast forward several months, and Ashley has found herself here making her own contributions to both our work and office culture. She has enjoyed the variety of work she has gotten to do, from meeting clients on death row to jury investigations to reviewing court records for potential legal claims. Ashley has also appreciated the intentionality with which we treat our interns, citing our open-door policy, weekly check-ins, and the “Interns of Color” program as highlights.

Deksyos has likewise been an invaluable member of our summer crew. From an early age, Deksyos has been motivated to work with communities that have intersecting identities tied to race, class, and disability. For Deksyos, the death penalty is the largest signifier of how our country treats the disadvantaged. He has sought mentorship from the likes of Bryan Stevenson and now the staff at CDPL in his journey towards advocacy in this space. Like Ashley, Deksyos has enjoyed the variety of work he has been doing, particularly meeting with clients. This summer was the first time Deksyos ever visited an individual on death row. He was struck by the hospitality his client extended to a stranger, openly sharing about his life, his growth, and his current interests and passions. An out-of-towner, Deksyos has also getting to know Durham and the nature and community it has to offer.

We are honored that the Marshall-Motley Scholars Program would trust us with their scholars and grateful to Ashley and Deksyos for offering so much of themselves to us and our clients . We are excited to see their paths as advocates unfold and look forward to hosting future Marshall-Motley Scholars.

What I learned in 15 years working to end the death penalty

Kristin Collins is the outgoing director of public information at the Center for Death Penalty Litigation. As she prepares for new adventures in sailing and writing, we asked her to reflect on her time at CDPL.

In my nearly 15 years of working in death penalty communications, my goal was always to change other people’s hearts and minds. With the stories I told, I aimed to shape policies and public opinion — to help create a society that no longer sentences people to execution. Now, as I prepare to leave my job at the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, it’s difficult to measure how much success I had in those areas. In the end, there is only one outcome I feel truly certain about: This work transformed my heart and mind.

I grew up on a cul-de-sac in suburban Pennsylvania in a family that was the opposite of counter-cultural. My main activities outside of school were watching TV and going to the mall. If I learned anything about the American criminal “justice” system, it was that anyone who got arrested must have done something to deserve it. In other words, I’m the last person you might have expected to end up marching in the streets to end the death penalty.

Before I joined CDPL, I spent 13 years as a newspaper reporter, where I began to learn about the world beyond my cul-de-sac. At my first job in the late 1990s, I covered crime and courts in Lenoir County, North Carolina. The injustices were so glaring that even I couldn’t help noticing them. One of my first big assignments was to cover the capital trial of a Black man the prosecutor described repeatedly as a “drug dealer from New York.” At the end of the trial, I wasn’t persuaded that he was guilty. Yet, he got a death sentence and remains on death row today. When I moved to the News & Observer in Raleigh, I covered immigration, which gave me the opportunity to meet undocumented immigrants, refugees, and horribly exploited workers. Yet, despite all the stories I wrote, my real education didn’t begin until 2010, when I started as a part-time contract writer for CDPL.

I was hired just as the first round of Racial Justice Act claims were filed. My job was to sort through clients’ stories and find those that best exemplified the death penalty’s racism. It was quite an initiation for a person who barely understood the meaning of the term “systemic racism.” As I read case summaries and legal pleadings, the facts of the crimes leapt from the pages, obscuring my view of the humanity beneath. Yet, people like Gerda Stein and Ken Rose didn’t write me off as clueless. Instead, they spent long hours explaining how the legal system works, describing the backgrounds of our clients, helping me see that crime springs not from evil but from pain.

A few personal stories Kristin shared over the years:

- A sermon at the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Raleigh

- Op-ed: Jurors sent an innocent man to death row. Now they ask: “Where did we go wrong?”

- Blog post: I’m still learning what freedom really means for the wrongfully convicted

In 2014, I got the ultimate lesson in the death penalty’s cruelty. I was in the courtroom when Henry McCollum and Leon Brown were declared innocent more than 30 years after being sentenced to death. These two brothers were still children when they were stolen from their home and bullied into confessing to a rape and murder they had nothing to do with. It was my privilege to help Ken Rose express his feelings about having a client exonerated after three decades on death row.

I’ve had countless experiences working for CDPL that have reshaped my view of the world. Racial equity training changed not just my understanding of American history but of my own family’s story, revealing how whiteness influenced every aspect of my life. Visiting death row showed me the kindness, creativity, and deep humanity of the people we sentence to die. Hearing their life stories, I became aware of the immense suffering that our society inflicts on poor families, especially children.

However, the most transformative experience was one that accrued slowly. It came from watching my coworkers and fellow advocates. The reality of working against the death penalty in the American South is that, more often than not, you lose. Yet, my colleagues remain undaunted, refusing to give up even after heartbreaking losses, even when cases stretch on for decades, or when leaders fail to hear our calls for action. They work without any expectation of accolades or personal gain. They take the hardest cases without complaint. They not only defend the most despised people in our society, they love them.

During my years at CDPL, I contributed to many projects of which I’m proud: Racist Roots, the statewide Racial Justice Act litigation, the campaign calling on Gov. Roy Cooper to commute death row, which resulted in 15 people being resentenced to life. However, what I take with me is not a list of accomplishments, but a few key lessons I learned from this community: Err on the side of offering grace and forgiveness. Put ego aside. Work for what’s right rather than what’s possible. Listen deeply to people’s stories. Always keep widening the circle of compassion. And never forget that our capacity for love is our greatest power.

‘Beyond words’: CDPL’s Shelagh Kenney on telling four death row clients they received clemency

Shelagh Kenney is CDPL’s deputy director. She has been a capital defense attorney since 2001 and represents eleven people on North Carolina’s death row. That number is significantly smaller than it was just a few months ago. On Dec. 31, Gov. Cooper granted clemency to 15 people on death row, commuting their sentences to life without parole. Eleven of those were CDPL clients and four of them were represented by Shelagh, along with co-counsel. We talked with Shelagh about what Gov. Cooper’s action meant for her clients and for the future of the death penalty.

You had four clients who received clemency from Gov. Cooper in December. Tell us how this came to be.

These commutations were the result of a lot of hard work by a large group of organizations and individual attorneys. Just to name a few of the organizations that worked for this outcome: the N.C. Coalition for Alternatives to Death Penalty, the N.C. Council of Churches, the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, the ACLU of North Carolina, and the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project. That list should also include my co-counsel and many other attorneys across North Carolina who worked diligently to submit clemency petitions.

These grants of clemency grew out of decades of effort to tell the stories of the death penalty’s many injustices. Of the cases Gov. Cooper selected for clemency, nearly all were tried in the 1990s. There have been advances in forensic science, in quality of counsel, in our understanding of eyewitness identification. Certainly, racism is inextricably intertwined with many of them. All of those are flaws we’ve worked to spotlight.

It’s also clear to me that Gov. Cooper took claims of innocence seriously, which is another issue CDPL has brought to the forefront. A number of those whose sentences were commuted raised issues related to wrongful convictions, including my client, Elrico Fowler. This is a case where there’s no forensic evidence and it’s clear that the eyewitness identification is flawed by modern standards. I’m grateful to the governor for recognizing the strength of those claims, even if we were unable to upend the convictions entirely.

Can you tell us why this grant of clemency was historic for NC?

North Carolina is one of the top five states in terms of death sentences, so we can’t compare ourselves to states like Oregon where governors have cleared death row on their way out of office. Gov. Cooper reviewed individual clemency petitions for 90 people on death row, and he found evidence of serious problems. In his statement announcing the commutations, he remarked on several important issues, such as the influence of race on capital trials and the sentencing of people with diminished mental and intellectual capacity.

Gov. Cooper is the only North Carolina governor who has ever commuted a group of death sentences because of systemic problems with the death penalty. In the 50 years since modern death penalty statutes have been in place, North Carolina governors had granted mercy to only five people on death row, and each one of those was an individual decision made on the eve of an execution. Gov. Cooper’s decision to make a significant grant of death row clemency was a huge step forward for North Carolina.

How does this change the lives of your clients? What does it mean for them to be off death row?

For all four of my clients, the weight of a death sentence was ever-present. To be freed from that has been life changing. Elrico called me recently, and he’s been moved to a prison where he is now able to have contact visits. He told me he’d been able to hug family members that he had not hugged in more than twenty years. My client Iziah Barden told me he was able to walk in the snow for the first time in twenty-five years.

All of my clients who received clemency have expressed a desire to continue to improve themselves, to contribute, to be more a part of their families and of the prisons where they live. Now they’ll have more opportunities to get jobs, to take classes. Elrico is going to study for his GED. He’s wanted to get his GED for decades, and he did not have the ability to do that on death row.

As a criminal defense attorney, you had a lot of choices about who you could spend your career representing. Why did you choose to work with death sentenced people?

In law school, I got involved with a death penalty clinic and began to feel that the death penalty was our country’s greatest human rights violation. And I realized there was something I could do about it. I could represent people through all of their appeals. This work can be draining, but I get to have relationships with clients over decades, and I find that life affirming and sustaining. At this point, I’ve known clients longer than I’ve been married and represented clients longer than my teenage child has been alive.

Getting to know my clients’ stories so very deeply has made me recognize that we all have human frailties. I truly believe we’re all a couple steps away from being in the same place. There are times when I think, compared to public defenders or other attorneys with much higher case loads, the fact that I represent eleven people is so small. But to me, to save one life is to save many. I want to be part of a society that recognizes the humanity of each and every person. It’s my life’s work to represent those most vulnerable.

How did it feel to give your clients the news that they had received clemency?

Going to Central Prison on December 31 to share the news with four clients was beyond words. The palpable relief that I could see in their faces was so immediate. One of my clients was so emotionally overwhelmed that I think it was only a couple days later that he felt like he’d been able to process it. For another client, it was so important to have that recognition that he was deserving of mercy. But I also saw that some of them were very worried about the people they would be leaving behind on death row. They have friends still facing execution, and that weighs on them.

One of your clients who received clemency was Hasson Bacote, who just won a major victory under the Racial Justice Act. Can you tell us a little about the racism you uncovered in his case, which compelled Gov. Cooper to act even before the judge made his decision?

Since the passage of the North Carolina Racial Justice Act in 2009, I’ve worked with an amazing team of attorneys to uncover racism in North Carolina’s death penalty cases. Most recently, during an evidentiary hearing in Mr. Bacote’s case, we brought to light shocking evidence that race played a key role in his trial and sentence. It’s far too extensive to summarize here, so I’ll just point out a few of the most egregious facts we uncovered.

First, the assistant district attorney who prosecuted Mr. Bacote called him a “thug” in front of the jury. This was a term he understood had racial connotations; he admitted that under oath. This same prosecutor called my client Iziah Barden, who fortunately also got a commutation, a “piece of trash.” He referred to other capital defendants as “predators of the African plain.” When we combined the data for all his trials, that prosecutor struck Black jurors at ten times the rate of white jurors. In Johnston County where these trials took place, every single Black defendant who proceeded to a capital sentencing hearing got a death sentence. But if you were white, the chances of death were only 50-50. Racism just infused those cases.

Tell us about some of your clients who remain on death row. Do you think Gov. Cooper picked the 15 most deserving people to receive clemency?

Certainly not. There are many other people on death row who are just as deserving of commutation as those Gov. Cooper selected. We have many clients with strong claims about their intellectual capacity who should not be executed. There are many other cases with shocking instances of racism. There are people who were severely mentally ill at the time of their crimes. There are people who were barely over 18 when they committed their crimes. There are also many people now on death row who are elderly and frail, and their ability to care for themselves is less and less each day. They are not a threat to others, they are not a threat to staff, and they could be serving their sentences in a place where they could get better care.

Of course, I wish Gov. Cooper had granted clemency to everyone who applied. Yet, that shouldn’t diminish the action he did take. It showed me that we can speak to people in positions of power and they can hear the real truth about our clients. It gives me great hope that future governors in North Carolina and across the country can be moved by our clients’ stories.

Another racial justice victory — and what it means for our work to end the death penalty

A letter from CDPL Executive Director Gretchen M. Engel:

You may have already heard that, on Feb. 7, CDPL and its partners achieved a tremendous victory under North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act. (Read our press release.) Our client Hasson Bacote became the fifth person to prove that his death sentence was poisoned by racism. The ruling didn’t affect Mr. Bacote’s sentence because he had already received a commutation to life without parole from Gov. Cooper. Nevertheless, this ruling carries great significance in our work to end the death penalty.

Superior Court Judge Wayland Sermons didn’t just agree with us that racist jury strikes denied Black people a voice in capital juries, the same finding that Judge Gregory Weeks made more than a decade ago in the cases of four Cumberland County clients. Judge Sermons went further, finding that race affected who was sentenced to death. He wrote that, in Johnston County, “Black defendants like Mr. Bacote have faced a 100 percent chance of receiving a death sentence, while white defendants have a better than even chance of receiving a life sentence.” Judge Sermons called out Mr. Bacote’s prosecutor, Gregory Butler, who also prosecuted others who remain on death row, for routinely “denigrating Black defendants in thinly veiled racist terms.” Even after a judge warned him not to, Mr. Butler referred to Black defendants as “predators of the African plain.” He called another Black man a “piece of trash.” In Mr. Bacote’s case, he used the insult “thug,” and admitted at the hearing this spring that he knew this was a racially coded term. It was deeply gratifying to see a judge acknowledge this discrimination after decades of watching prosecutors face no consequences for using racist tropes against our clients.

Perhaps most importantly, Judge Sermons acknowledged that Mr. Bacote’s case “fit within a long history of racial discrimination.” As we litigate capital cases across North Carolina, it’s clear that most judges and prosecutors want to believe our modern death penalty system has no link to this state’s history of slavery, lynching, and segregation. Yet, as we revealed in our groundbreaking project Racist Roots, the modern death penalty is deeply entangled with white supremacy and remains a tool to enforce racial hierarchy.

In his ruling, Judge Sermons reckoned with this truth and did not mince words. He acknowledged that the exclusion of Black people from juries is linked to their exclusion from voting rights. He described how historical practices of barring Black people from jury pools evolved into prosecutors’ modern practice of using peremptory strikes to disproportionately exclude Black citizens. He also clearly noted the link between racial terror and the death penalty. Judge Sermons wrote, “The historical evidence received by this Court reveals that racial intimidation and discrimination continued in Johnston County for many years, including right outside the courthouse doors. Into the early 2000s, Johnston County remained known as ‘Klan country.’ This reputation stemmed, in part, from the landscape itself: For years, the major entrances to towns such as Smithfield, Princeton, and Benson, were marked by a series of imposing billboards advertising the county as home to the Ku Klux Klan.” (Read the full order.)

It’s hard to describe how stunning and heartening it was to see a judge acknowledge these deep truths about the death penalty. It was certainly emotional for Mr. Bacote, who lived under a racist death sentence for 15 years. We hope this ruling will encourage North Carolina’s leaders to take a close look at the cases of the 121 people who remain on North Carolina’s death row. Slowly but surely, we are accruing a mountain of evidence that the modern death penalty is not just descended from racism, but that it cannot escape its racist roots.

Judge finds Johnston County’s death sentences poisoned by racism

SMITHFIELD, NC — Today, a Johnston County judge found that race played a key role in the death penalty trial of Hasson Bacote, influencing both the makeup of his jury and the decision to sentence a Black man to death. Superior Court Judge Wayland Sermons also found that racial discrimination extends beyond Bacote’s case, poisoning all death sentences in Johnston County and the prosecutorial district that also includes Harnett and Lee Counties. (Read the judge’s order here.)

The decision was the result of a two-week hearing in early 2024 under North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act, which included detailed testimony from statisticians, social scientists, historians, and legal scholars.

“We are grateful that Judge Sermons carefully weighed the evidence and found that the administration of the death penalty in Johnston County remains deeply entangled with racism,” said Gretchen M. Engel, executive director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, which along with the ACLU and the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund brought forward Mr. Bacote’s Racial Justice Act claim. “This decision is a damning indictment of the death penalty, and should serve as a call for every North Carolina death sentence to be reexamined. North Carolina must never carry out another execution tainted by racial discrimination.”

The ruling comes on the heels of Gov. Roy Cooper’s historic grant of clemency to 15 people on death row, including Mr. Bacote. Judge Sermons’ decision will not affect Mr. Bacote’s sentence because he has already been resentenced to life without parole. However, the ruling has significance for the 121 people remaining on North Carolina’s death row because it makes findings that go far beyond Mr. Bacote’s case.

“I am deeply grateful to my family, my lawyers, the experts, and to everyone who fought for justice—not just in my case, but for so many others,” Mr. Bacote said in a statement made through his attorneys. “When my death sentence was commuted by Governor Cooper, I felt enormous relief that the burden of the death penalty — and all of the stress and anxiety that go with it — were lifted off my shoulders. I am grateful to the court for having the courage to recognize that racial bias affected my case and so many others.”

Among the evidence Sermons cited in his order were statistical studies proving race discrimination in jury selection. The judge also considered prosecutors’ racist notes and disparate treatment of white and Black potential jurors, as well as evidence about the history of discrimination in Johnston County and statewide. All of this evidence showed Black people were disproportionately denied a voice in the justice system and, in front of majority white juries, prosecutors often felt free to invoke racist tropes and slurs.

In Mr. Bacote’s case, prosecutor Greg Butler struck prospective Black jurors at more than three times the rate of white potential jurors and referred to Mr. Bacote as a “thug” during the trial. In other cases he prosecuted, Mr. Butler referred to Black defendants with terms including “piece of trash” and “predators of the African plain.” It is no coincidence that all eight of the Black men tried capitally in Johnston county under modern death penalty laws have been sentenced to death. By comparison, only about half of white defendants in the county received death sentences.

Engel said she regretted that Gov. Cooper did not have the benefit of Judge Sermons’ order when weighing clemency for those on death row, including four other men sentenced in Johnston County.

“Judge Sermons was very clear in his ruling,” Engel said. “The evidence of racism in the death penalty is simply too egregious to deny, and it extends far beyond any one case. It’s now up to our new governor and attorney general to take action to remedy the systemic racism of the death penalty.”

With 15 death row commutations, Gov. Cooper joins a majority of U.S. governors

For more information contact: Gretchen M. Engel, gretchen@cdpl.org, (919) 682-3983

Raleigh, NC — Gov. Roy Cooper today joined a growing list of governors who have taken action to limit the use of the death penalty with an announcement of 15 grants of clemency for people on North Carolina’s death row. It is the largest grant of death row clemency in North Carolina’s history.

Those who will now serve life without parole sentences include 11 clients of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation. Their cases involve evidence of serious flaws including racial bias, questions of innocence, and the use of the death penalty in cases of severe mental illness, intellectual disability, or young people whose brains have not fully developed. Among them is Hasson Bacote, who earlier this year brought forward groundbreaking evidence of the link between North Carolina’s death penalty and its history of racial terror in a hearing under the North Carolina Racial Justice Act.

CDPL is a member of the Racial Justice Act litigation team and has been part of a two-year campaign calling on the governor for death row commutations.

“We are deeply gratified that Gov. Cooper took our request for capital commutations seriously,” said Gretchen Engel, executive director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation. “It makes sense that governors are taking steps to prevent executions, given the hundreds of death row exonerations we’ve seen across the country and the overwhelming evidence of racism in capital trials.”

Every Democratic governor in a state with the death penalty has now taken at least some executive action to prevent executions, whether by imposing a moratorium, granting commutations, or supporting legislation. Republican governors in Tennessee and Ohio have also halted executions. (See a state-by-state overview of the death penalty here.)

“I’m deeply grateful that North Carolina has now been added to the list, given that we have one of the largest death rows in the nation and some of the most glaring evidence of racism in capital sentencing that’s ever been presented in a courtroom,” said Jay Ferguson, a lead attorney on Mr. Bacote’s case and a member of CDPL’s board of directors. “In light of the sweeping evidence of race discrimination that we brought forward under the Racial Justice Act, North Carolina must never allow another execution.”

A Gallup poll released in November found U.S. death penalty support at a 40-year low, with a majority of Millenials and Gen Z now opposing it. In North Carolina this year, there were three capital trials but no new death sentences because prosecutors seek the death penalty much less frequently and most juries vote for life even in the most severe cases.

“People are realizing what those of us who work in this system have known for decades,” Engel said. “The death penalty is a deeply unjust and ineffective system that plays no role in keeping communities safe. I hope our elected officials will follow Gov. Cooper’s lead and continue to move North Carolina toward more effective and humane responses to crime.”

North Carolina’s death row remains the fifth largest nation with 121 people awaiting execution. Attorneys at CDPL represent about half of them.

Thank you, President Biden, for courageous leadership to prevent federal executions

A statement from Gretchen M. Engel, executive director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation:

“CDPL commends President Biden for his courageous leadership today in commuting nearly all federal death sentences to life terms. At one time, CDPL worked on the cases of all three men on federal death row from North Carolina: Marcivicci Barnette, Richard Jackson, and Alejandro Umana. We have seen first-hand that the federal death row has the very same flaws that haunt North Carolina’s death row. It is deeply racist and a majority of those facing execution are people of color, some of whom were sentenced by all-white juries. Many federal death sentences are decades old and reflect different standards of justice. In such a deeply flawed system, there is the ever-looming threat of executing an innocent person.

“We urge Gov. Cooper to take a similar action to reduce the size of North Carolina’s death row. The threat of executions resuming in North Carolina is every bit as urgent as it was at the federal level. It will take bold leadership to move us away from the archaic and racist death penalty.”