Closing arguments scheduled in a landmark case that put the death penalty’s racism on display

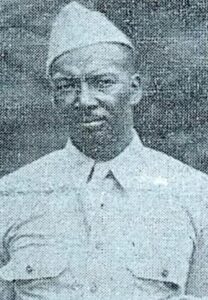

SMITHFIELD, NC — On Wednesday, August 21 at 10 a.m. at the Johnston County Courthouse, closing arguments will be held in the case of Hasson Bacote, who is challenging racial bias in death penalty cases across North Carolina. Bacote, a Black man who has spent 15 years on North Carolina’s death row, presented evidence that prosecutors illegally excluded Black citizens from his jury, as well as the juries of North Carolina’s other 135 death row prisoners.

Now, a Johnston County judge must decide whether Bacote should be resentenced to life in prison without parole because race infected his death sentence.

“This case boils down to a simple question: Will death sentences tainted by discrimination be carried out in North Carolina?” said Gretchen M. Engel, executive director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation. “The evidence is very clear that the modern death penalty is still directly tied to our state’s history of racial terror, and that it continues to produce biased outcomes.”

Bacote’s is the lead case under the North Carolina Racial Justice Act, a 2009 law that allowed death-sentenced people to bring forward evidence that race affected their trials and sentences. His is the fifth case to be heard under the law, and more than 100 other death row prisoners have pending claims. Bacote is represented by the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, the ACLU Capital Punishment Project, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and Durham attorney Jay Ferguson.

In late February and early March, attorneys for Bacote presented extensive evidence of a race-conscious death penalty process. Statistical experts testified that, across North Carolina, potential Black jurors are more than twice as likely to be excluded from death penalty trials as similar white jurors. Jury selection notes from trials across the state revealed that prosecutors were keenly aware of race as they made their decisions about which jurors to exclude.

In Johnston County, where Bacote was tried, jury discrimination was compounded by other racial disparities. Bacote is one of eight black men tried capitally in Johnston since the 1970s. Every one of them received the death penalty; in contrast, only about half of white capital defendants received death sentences. Bacote is also one of just 11 people in the state sentenced to death without any evidence that he intended or planned the killing; all 11 are people of color. During his trial, the prosecutor disparaged him using the racially coded insult “thug.” The same prosecutor referred to other black defendants as “predators of the African plain” and a “piece of trash.”

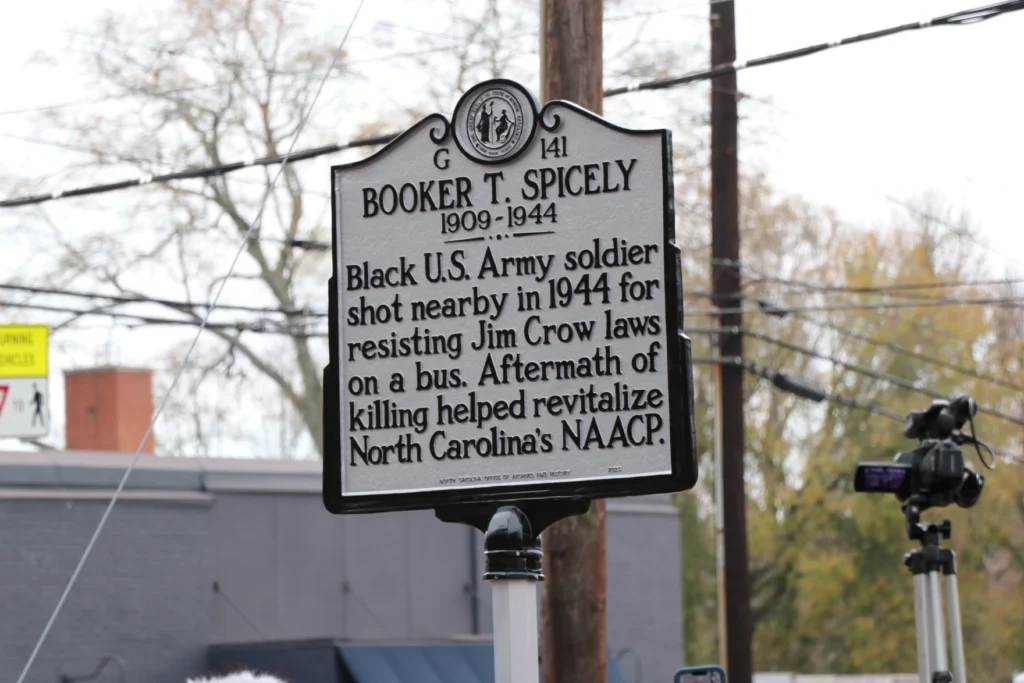

Historians and social scientists spoke to the ways that North Carolina’s history of racial terror and Jim Crow segregation continue to echo in modern courtrooms. In Johnston County, this connection is especially clear. Billboards promoting the Ku Klux Klan stood at the entrances to the county until the mid-1970s, and Klan activity was documented there until the 1990s. Egregious incidents of racist policing have gone unaddressed. Still today, the county has never elected a Black county commissioner, and a sheriff who made openly racist statements in the News & Observer remains in office.

Closing arguments will be held on the second floor of the Johnston County Courthouse. They will also be livestreamed on WRAL.com.

More on the case of Hasson Bacote: