CDPL attorneys Elizabeth Hambourger and Vernetta Alston were part of the team that won a life sentence for Nathan Holden in Wake County on March 3. The jury rejected both the state’s claim that the murder was premeditated and that the death penalty was warranted. It was the eighth capital trial in a row in which a Wake County jury chose life without parole over a death sentence. Here you can watch Elizabeth Hambourger give her moving closing argument, in which she asked the jury to save her client’s life.

CDPL client resentenced to life due to racial bias in court

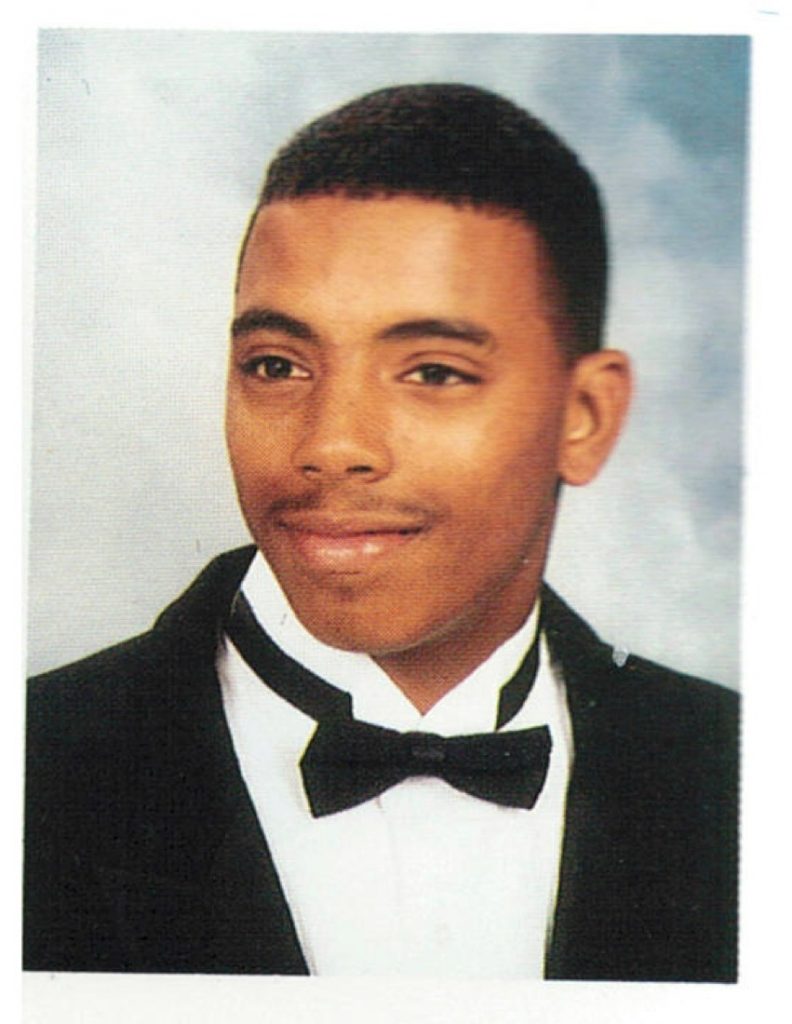

Last week, a CDPL client who spent nearly 20 years on death row was re-sentenced to life in prison without parole. This was a sane resolution to a senseless and much-regretted crime committed by a deeply troubled teenager.

Last week, a CDPL client who spent nearly 20 years on death row was re-sentenced to life in prison without parole. This was a sane resolution to a senseless and much-regretted crime committed by a deeply troubled teenager.

Phillip Davis was re-sentenced with the full of support Buncombe County District Attorney Todd Williams, who acknowledged unfairness in Davis’ case. “Our system has built-in checks on abuses such as discrimination and prosecutorial misconduct. When the system is not allowed to work as it’s naturally intended to, that’s when you have a problem,” Williams told the Asheville Citizen Times.

Davis was represented by Shelagh Kenney, CDPL’s Director of Post-Conviction Litigation, and Mark Kleinschmidt.

Davis was among the more than three-quarters of N.C. death row inmates who were sentenced to death before 2001, when vastly different laws led to dozens of people being sent to death row each year. Now, with executions on hold for a decade and juries imposing an average of only one death sentence a year, they languish on death row year after year.

Settling these old cases for sentences of life imprisonment with no possibility of parole would end costly appeals and ensure that defendants are never released from prison — while giving a punishment that is far more fitting with North Carolina’s current standards of justice. Once in general population, inmates cost less to house and can get jobs that allow them to contribute to society.

In Davis’ case, he was just four months past the age that would now make him ineligible for the death penalty when, as a high school senior, he killed his cousin, Caroline Miller, and his aunt, Joyce Miller, after an argument. Davis was living with them because his mother — a lifelong drug addict who had subjected him to a traumatic childhood — was in prison.

Davis, whose IQ puts him in the range of borderline intellectual functioning, immediately accepted responsibility for his crimes and expressed deep remorse. He voiced his sorrow and regret for his actions again in court last week, his voice choked with emotion: “To family members and anyone who knew Joyce and Caroline, they were two very special people who were loved by a lot of people including myself. I regret everything that happened and it’s something I’ll regret for the rest of my life.”

The prosecutor who agreed to his new sentence acknowledged that race wrongly played a role in selecting the all-white jury that sentenced Davis to death in 1997. It is illegal to strike jurors based on race, and in 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed that in the strongest terms ever.

The problem was compounded when prosecutors in Davis’ case took the unusual step of shredding many of their notes from jury selection, making it impossible to examine them for evidence of racial bias.

The victims’ family members said they were satisfied with the life sentence. They have worked over many years to rebuild their relationship with Davis, and his new sentence allows the family’s healing to continue.

It’s a resolution that makes sense for all involved.