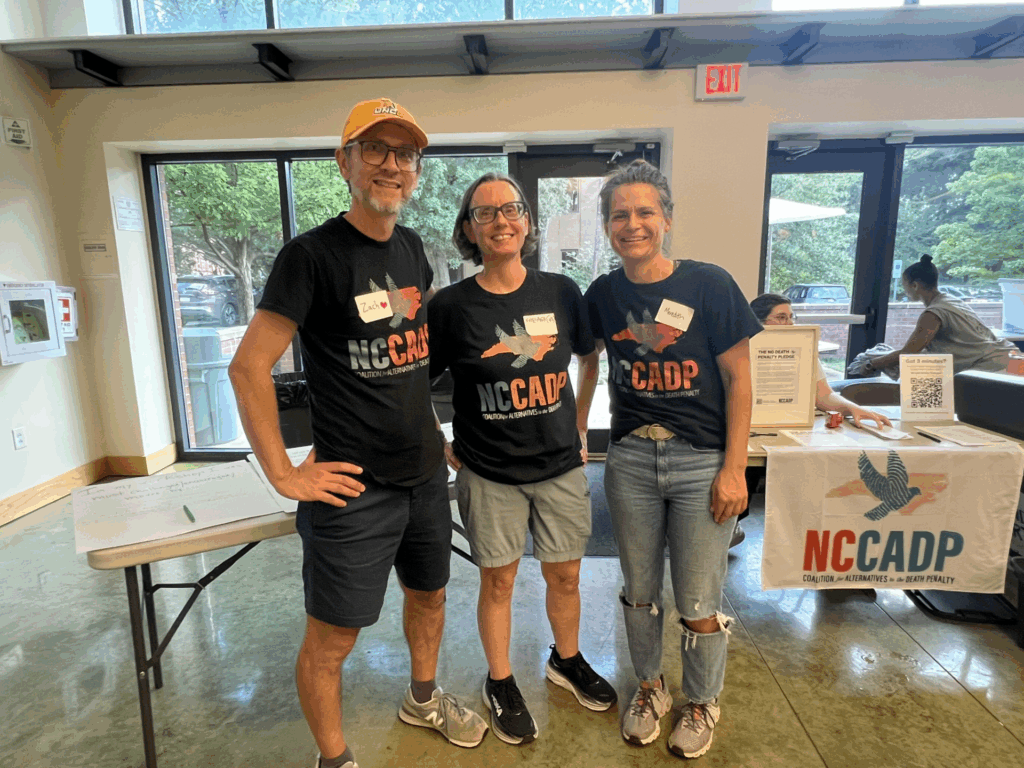

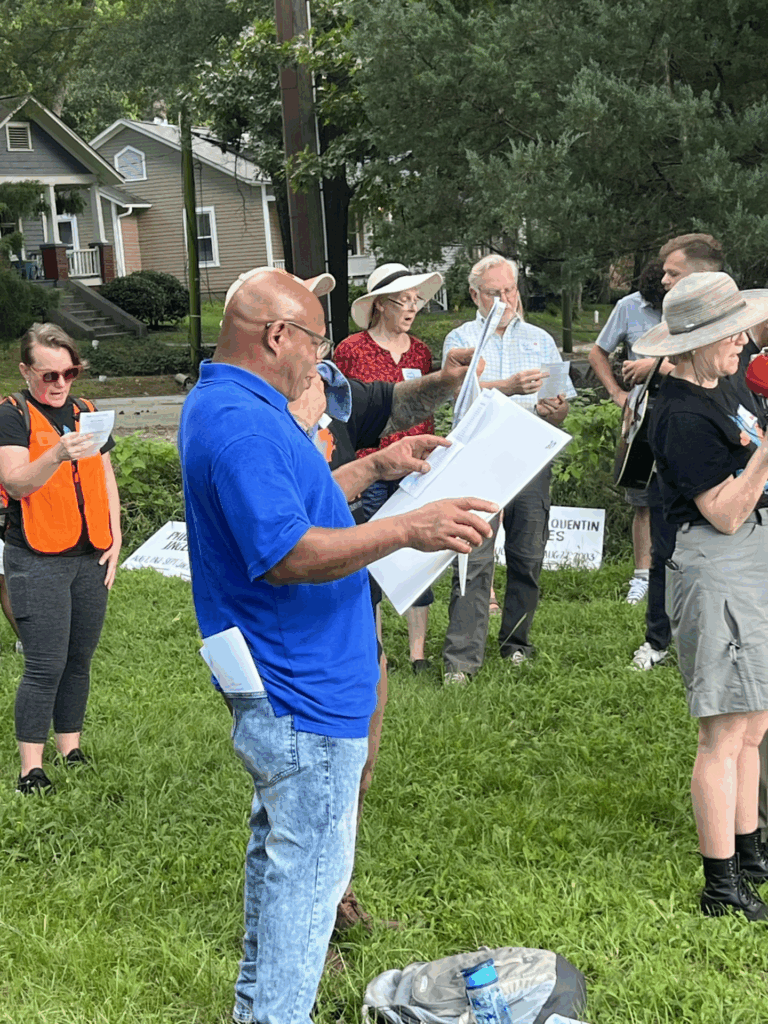

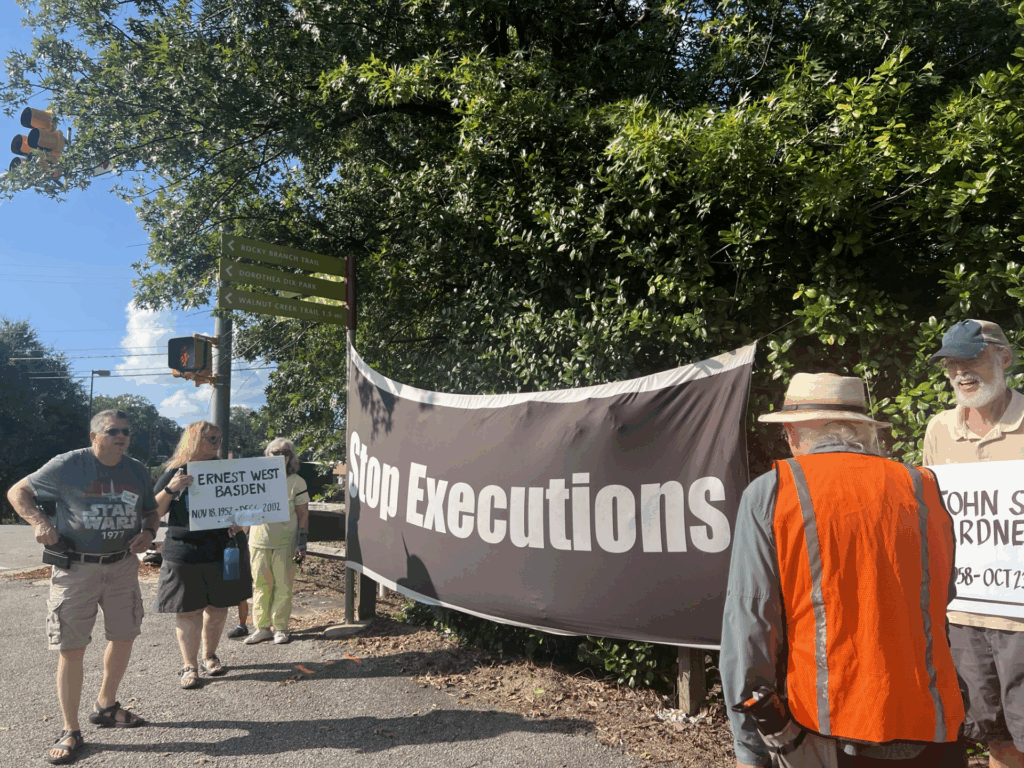

On Saturday, August 16, a few of us from CDPL gathered at Pullen Memorial Baptist Church in Raleigh to join NCCADP’s day of workshops, remembrance, and advocacy. There was an eclectic mix of people, ranging from individuals exonerated from death row, family members of people who have been executed, and those motivated by religious persuasion. As we walked from the church to Central Prison, where 120 men sit on death row, we carried signs bearing the names of the individuals who have been killed by the state of North Carolina and then read them out loud together.

It would be remiss of me not to acknowledge that each name lifted up represents multiple deaths, albeit persons killed by different means. We do not forget those names unsaid. Rather, when we remember those killed or condemned to be killed by the state, we lift up all victims of violence, steadfast in our belief that violence of any kind only breeds further harm. When we practice this unwavering sense of dignity in the other, we cultivate the compassion and empathy needed to break the tenacious cycle in which we find ourselves.

Glen Edward Chapman was one of the exonerated men who walked with us on Saturday. When I asked him how he thought about the victims in his case, he told me he always takes care to mention their names whenever he speaks publicly, recalling with disdain that the state consistently referred to them as simply “prostitutes.” The call for death penalty abolition is not one that overlooks victims, but one that sees past the deceiving binary between victims and offenders.

Having known Ed for a couple of years now, I have heard him reflect on the community he built during his 13 years on death row. Many in his situation, innocent and living with men convicted of murder, might fight to distinguish themselves from the others. Instead, Ed talks fondly of the relationships he developed, even considering some of the men his family. In that vein, he told me how painful it was whenever someone was executed. In the moments leading up to an execution, Ed and the others held a memorial service for them, going around and saying a cherished memory of the brother they were about to lose. At 2:00 a.m., the approximate time of execution, Ed would point towards his window and say, “I’ll see you soon.”

Against this backstory, I watched Ed read the names in the relentless August heat, and I considered the weight he must carry.

At the same time, just on the other side of the Triangle in Chapel Hill, Lynden Harris, founder and director of Hidden Voices, was on the eve of premiering A Good Boy. Harris spent time on death row as a volunteer, conducting writing and story-telling workshops. Much like Ed, her time there led her to what some may characterize as an unexpected sense of connectedness and insight. Harris would first write Right Here, Right Now: Life Stories from America’s Death Row, a collaboration between herself and over 100 people on death row across the country. Based on the conversations it generated, Harris decided to write a piece centered on the perspectives of individuals with loved ones on death row, and A Good Boy was born.

The musical is set in the waiting room at Crossroads Correctional, where two mothers and a male family member wait to speak with their loved ones on death row under the watchful eye of an over-worked corrections officer. A fourth visitor comes to retrieve a picture of herself with her brother, who was executed the night before. Amidst the helplessness and uncertainty they experience as they wait, the visitors’ conversations amongst one another and with the guard reveal harrowing truths about capital punishment, our carceral system, and how they both impact and are impacted by complex social fabrics. These conversations also illuminate a side of life on death row outsiders don’t get to see, such as diverse interests, including NPR, jazz, and politics, religious conversions, and friendship.

The main message crystallizes, though, through an unlikely character: the corrections officer. While it may seem like the guard is removed from the world of pain and suffering inhabited by the visitors and their incarcerated/executed loved ones, he shatters this illusion when he starts talking about his own childhood. He shares just enough details to expose the hatred and desire for vengeance he harbors towards his father, a vitriol that appears to overlap with the disdain he carries for those incarcerated at Crossroads Correctional. As the audience learns more about each character, they come to see that humanity is a web of brokenness, and the path to healing lies not in retribution, but “in a little mercy and a whole lot of grace,” the refrain of the musical’s last number.

Mercy and grace, however, do not erase pain and suffering. Nor are they incompatible with public safety. Creating safe spaces for healing is hard work. But taking the time to remember and reflect on one another’s humanity and the humanity of those to whom the basic right of breath has been denied, not to mention those who love them, might be the best place to start.

So thank you to NCCADP, Ed, and Hidden Voices for lifting up the humanity of our clients and their loved ones. We are all the better for it.