Discrimination based on personal conviction

In order to sit as a juror in a capital case, you have to be “death qualified.” This means you will be asked whether you would ever sentence someone to death, or if you are unable to do so based on a moral, religious, or any other type of belief. Individuals who fall into the latter category are not “death qualified” and can be dismissed from jury service accordingly.

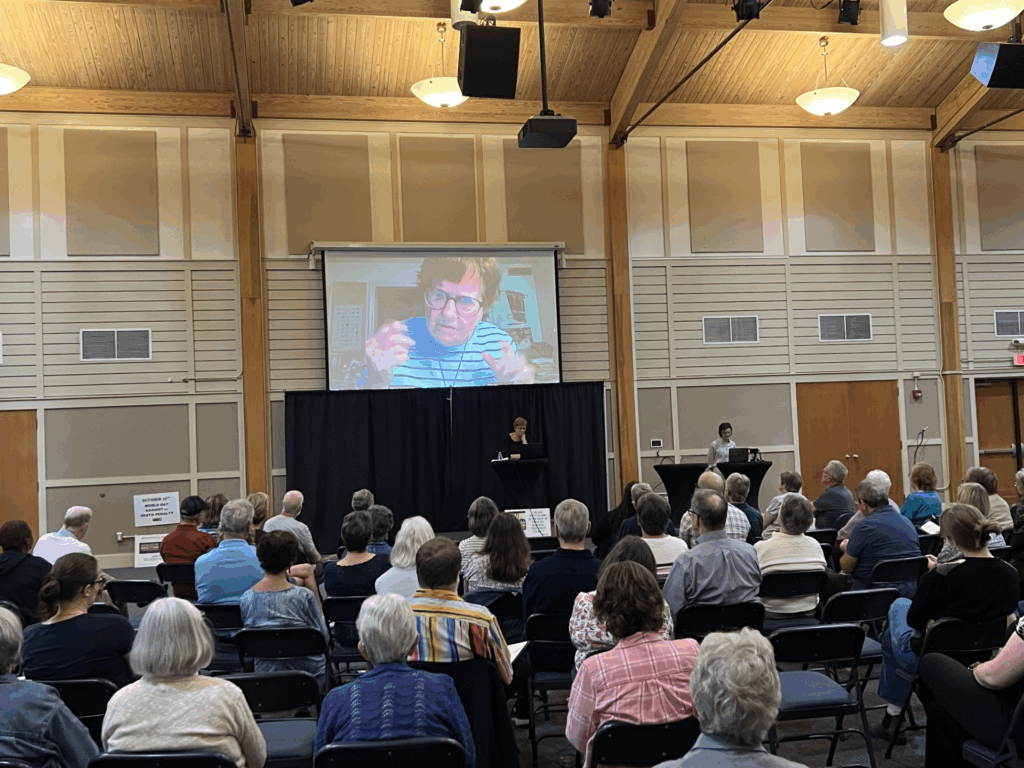

One religious group that is often impacted by death qualification is Catholics. On Wednesday, September 17, Catholics for Abolition in NC (CANC) hosted Sister Helen, author of Dead Man Walking and nationally renowned advocate for death penalty abolition. She spoke via zoom about her personal journey into anti-death penalty work and the broader movement within the Catholic Church. Sister Helen was the spiritual adviser to six men on death row, offering companionship, prayer and spiritual guidance up until the time she would witness each of their executions.

Sister Helen’s experiences with the men on death row, the loved ones of their victims, and her growing understanding of the Christian faith motivated her to push the leaders of the Catholic Church to take an absolute stance against it. After four decades of advocacy, she and her co-laborers finally succeeded. In 2018, Pope Francis announced a revision to the Catechism of the Catholic Church that opposes the death penalty in all circumstances, eliminating previous exceptions. The Pope publically declared that the death penalty is “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person” and can no longer be justified by the need for public safety.

As such, Catholics that strictly adhere to Catholic doctrine may be rendered unqualified to sit on capital juries. Non-Catholics compelled by Sister Helen’s powerful narrative and moral principles that affirm the inherent worth of all people, the potential for redemption of all people, and the notion that neither true healing nor true justice can come from inflicting harm on others, may also be precluded from doing what otherwise would be characterized as their civic duty.

Such a system is problematic for many reasons. Research has shown that death qualified juries are more likely to convict. This implies that individuals facing the death penalty don’t get the same presumption of innocence as those charged with lesser crimes and/or who face a lesser sentence. In addition, one statistic often used to measure public support for the death penalty is how many capital juries actually sentence the accused to death. Not allowing people who oppose the death penalty to sit on capital juries causes these statistics to be misleading.

Finally, when certain categories of people are excluded from juries, the accused is not likely to get a jury of their peers. According to a 2023-2024 survey, 800,000 Catholics live in North Carolina. Some within the Catholic Church estimate that number has grown to one million. Listening to Sister Helen speak, I looked at the others in the room wondering what will happen as the Catholic movement to abolish the death penalty grows. These thoughtful and compassionate people deserve to have a say in whether their neighbors live or die.

As I write, House Bill 307 is sitting on Governor Stein’s desk. It threatens to hasten executions and allow for a variety of torturous methods of execution, including the firing squad, nitrogen gas, and electrocution. Some proponents of the bill cite the importance of honoring jurors’ decisions regarding the sentences of the 122 people on North Carolina’s death row. These proponents don’t consider who these juries consisted of, and, perhaps more importantly, who they excluded.

To keep in the loop regarding what’s happening at CDPL, please subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on LinkedIn and Instagram.